Regular Expression Search via Graph Cuts

Google used to offer a search engine called Code Search which let you use regular expressions to search code. I never thought Code Search was doing anything much more sophisticated than something along the lines of a fast, distributed grep until Russ Cox explained how it worked in a blog post and released codesearch, a smaller-scale implementation. Both the post and the code are fascinating – it turns out that Code Search was doing something much more sophisticated than a distributed grep.

The big idea in codesearch is an engine that translates a large class of regular expressions into queries that can be run against a standard inverted index. In this post, I’m going to describe a different implementation of such an engine using some of the same ideas in codesearch along with a well-known algorithm for finding the minimum-weight node cut in a graph. I think the result is a little bit simpler conceptually than the query-building technique that codesearch uses, particularly if you understand textbook regular expressions but don’t know a lot about the internals of any particular regular expression library.

The implementation I’ll describe is available as a Go package at https://github.com/aaw/regrams. It’s a few hundred lines of code and the benchmarks show it running only about 4-5 times slower than codesearch’s regular expression-to-query translation. Both engines run on the order of microseconds for individual queries, so a few times slower is still very usable for a search engine.

Trigram queries and regular expression search

First, a little background about codesearch’s approach to regular expression search.

Before it can process queries, codesearch creates an inverted index from all the

files you want to search. The index contains all overlapping substrings of length 3

(“trigrams”) that occur in any of the files.

If you index a file called greetings.txt which contains just the

string Hello, world!,

the resulting trigram index would contain entries for

Hel, ell, llo, lo,, o,_, ,_w, _wo, wor, orl, rld, and ld!.

When you look up any of those trigrams in the index,

you’ll get a list of files: greetings.txt and any other files that contain

the trigram you’ve looked up. At query time, codesearch extracts trigrams from the regular expression

and uses those trigrams to look up some candidate documents in the index.

The trigram queries used by codesearch are just trigrams combined with ANDs and ORs.

For a simple regular expression like Hello, codesearch might generate the trigram

query Hel AND ell AND llo. Looking that query up in the index would return all of

the indexed files that contain all three of the trigrams Hel, ell, and llo.

A more complicated regular expression like abc(d|e) might generate the trigram

query abc AND (bcd OR bce).

Sometimes there’s no good trigram query for a regular expression. This can happen

if the regular expression accepts strings of length less than 3. The regular

expression [0-9]+, for example, accepts strings of digits of length 1 and 2 so

we can’t use a trigram query to search for files that match that expression.

There also may not be a good trigram query if the regular expression accepts too many

different strings. [a-z]{3} is a short regular expression but it needs an enormous

trigram query with 17,576 trigrams OR-ed together to capture its meaning. If you leave

off any of those 17,576 trigrams from the query, you risk false negatives: files that

match the query but aren’t returned from your trigram query. You’d be better off

grepping files in most cases than running such a large query.

Finally, even when codesearch can come up with a good trigram query, it can get false

positives in its result set from the trigram index. The regular expression Hello’s trigram query

Hel AND ell AND llo matches not just files containing Hello but also files that

contain things like Help smell this fellow. Since false positives like this are

possible, a regular expression search based on trigram queries will need to

post-process trigram query results by running the regular expression over each file

that comes back. The goal, then, is just to generate a small enough set of candidate

documents so that the query generation, lookup in the inverted index, and post-processing

with the original regular expression runs much more quickly than exhaustive grepping over

files.

codesearch generates these trigram queries by parsing the regular expression using Go’s regexp/syntax, then analyzing the parsed regular expression and converting it into structures that describe what trigrams each portion of the regular expresssion can match. These structures are then combined based on a table of rules derived from the meaning of the regular expression operations involved. The structures maintained during this process keep track of several attributes of the pieces of the regular expression their analyzing: whether that portion matches the empty string as well as sets of trigrams that can match exactly as well as prefixes and suffixes. The whole process is quick and, along with some boolean simplification of the resulting trigram queries, generates succinct queries without false negatives.

Generating trigram queries with graph cuts

Instead of generating trigram queries by analyzing the structure of the regular expression, regrams transforms the regular expression into an NFA and analyzes that.

regrams uses an NFA with some extra annotations on the states. Getting

to an NFA from a regular expression in Go is pretty simple with the regexp/syntax

package: running Parse on the

string, then Simplify on the

resulting expression yields a normal form that’s easy to work with. regrams massages the

simplified expression into an even simpler form that’s closer to a textbook regular

expression, containing only concatenation (.), alternation (|), and Kleene star (*)

operations on literals and empty strings. This simplified expression

might match more than the original expression but it never matches less, so it’s fine

for generating a trigram query. Finally, regrams converts the simplified regular

expression into an NFA using Thompson’s algorithm.

Next, any state that has a literal transition gets annotated with a set of trigrams that are reachable starting from that state. There are a few exceptions: if we start collecting the set of trigrams but realize it’s going to be too large, we’ll bail out and the state will get an empty set of trigrams. Also, if we start collecting the set of trigrams but realize that you can reach the accept state of the NFA in 2 or fewer steps, we’ll bail out, since that means that we can’t represent the query from that node with trigrams. So we end up with annotations on some of the nodes in the NFA that describe trigram OR queries, but only on the nodes that are easy to write trigram OR queries for.

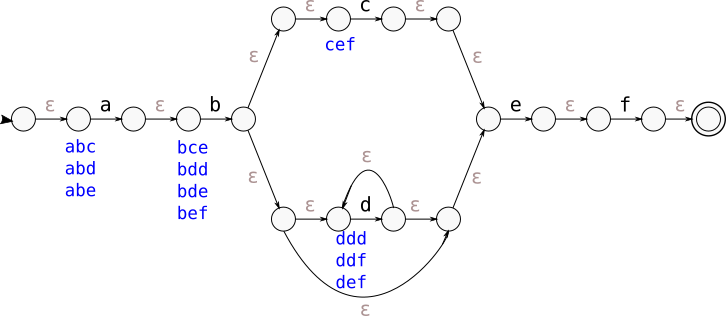

Here’s an example NFA for the regular expression ab(c|d*)ef with trigram set

annotations in blue below each node:

Notice that nodes with only epsilon transitions in the NFA above don’t get trigram annotations and nodes that can reach the accept state in fewer than 3 literal transitions like the node with the “e” transition and the node with the “f” transition don’t have trigram set annotations. Every other node is annotated with the set of trigrams that can be generated from that node by following an unlimited number of epsilon transitions and exactly three literal transitions.

Creating a trigram query from the NFA above is now just an exercise in applying the right graph algorithm. A good trigram OR query – one that captures a set of trigrams that must appear in any string matching the regular expression but is as small as possible – corresponds to a minimal set of trigram-annotated nodes in the NFA that, when removed, disconnect the initial state from the final state. In graph theory, a set of nodes that, when removed, disconnects two nodes s and t in the graph is called an s-t node cut. A node cut in our NFA separating the start and accept nodes corresponds to a complete set of trigrams that must be present in any string that matches the regular expression: there’s no way for a string to be accepted by the NFA but to go through one of the nodes in the cut.

In the NFA above, there are only two minimal node cuts that consist only of trigram-annotated nodes: the cut consisting of only the node with the “a” transition and the cut consisting of only the node with the “b” transition.

Once we’ve extracted a node cut consisting only of trigram-annotated nodes, we can just OR all of

the trigrams in the cut together and, by the argument above, we’ve got a valid trigram

query for the original regular expression: at least one of those trigrams must be

present in any string that matches the regular expression. Continuing with the

example above, depending on which cut we choose, we either

get the trigram query abc OR abd OR abe or the trigram query bce OR bdd OR bde OR bef.

At this point, our query is a single big OR defined by the cut and we’ve likely used relatively few of the trigram sets we’ve annotated the graph with. But because we’ve just isolated a cut, that cut splits the NFA (and also the corresponding regular expression) into two parts, and if we now clean up both of those two parts of the NFA a little, we can run the same cut analysis on each of two those parts recursively to extract more trigram queries. We just keep isolating cuts recursively until we can’t find a cut with trigram-annotated nodes, at which point there’s nothing good left to generate a query with. All of the OR queries we generate like this can be AND-ed together to create one final query.

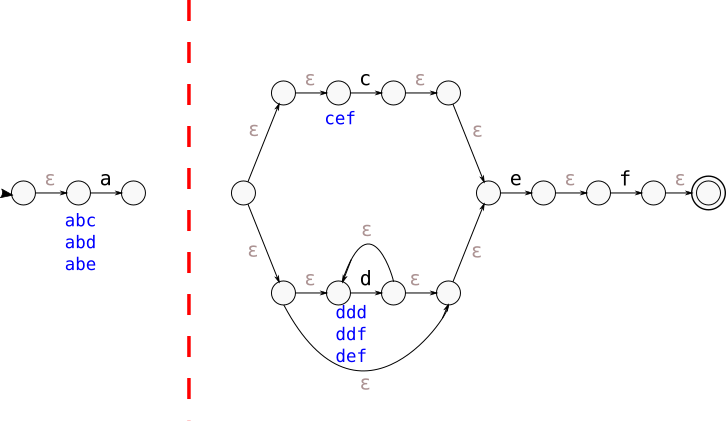

In the example NFA we’re working with, that means that if we choose the cut

with just the node with a “b” transition, it generates the trigram query bce OR bdd OR bde OR bef

and splits the NFA into two parts: the part with the “a” transition and everything

after the “b” transition node:

We can now recursively consider both sub-NFAs. We see a single cut in the

first NFA that generates the trigram query abc OR abd OR abe and no cut in the second

NFA that consists of just trigram annotated nodes: even if you remove both the

node with a “c” transition and the node with a “d” transition, there’s still

a path from the initial state in the sub-NFA to the accept state through the

lower-level epsilon-transition around the node with a “d” transition. Since there

are no cuts left in any of the subgraphs, our final trigram query for the entire

regular expression ab(c|d*)ef is all of the subqueries AND-ed together, which is

(abc OR abd OR abe) AND (bce OR bdd OR bde OR bef).

The fact that we couldn’t extract a cut from the second NFA is by design: that

NFA corresponds to the regular expression (c|d*)ef, which matches the string

ef that we can’t express with a trigram query.

Finding minimal node cuts

So how do you find a minimal cut consisting only of trigram-annotated nodes? If we label each node in a trigram-annotated NFA with the size of its trigram set or with “infinity” if it doesn’t have a trigram set, then we can frame the problem as a search for a minimum-weight node cut in the graph that separates the initial and final state. Because of the way we’ve set up the node weights, finding the minimum-weight node cut will tell us if we actually have a usable query: the cut can be used to generate a query exactly when its weight is non-infinite.

Finding a minimum-weight cut in a graph that separates two distinguished nodes is a tractable optimization problem and is especially easy in simple graphs like the NFAs that we get from regular expressions. Minimum-weight cuts are closely related to maximum weight “flows”, and if you ever took an algorithms course you may have run into the max-flow min-cut theorem that formalizes this duality. If you imagine a graph as a set of pipes of differing widths, flowing in the direction of the arrows between nodes, the max flow represents the most amount of fluid that can flow through the pipes at any point in time. The minimum-weight cut is a bottleneck that constrains the maximum flow you can push through.

The simplest way to find a minimum-weight cut, then, is to find a maximum-weight flow, which really boils down to initializing all nodes with capacities as described above (each capacity will either be infinite or the size of the trigram set) and then repeatedly finding a path that goes from the start node to the accept node through nodes of non-zero capacity. Every time we find such a path, we reduce the capacity of all nodes on the path by the minimum capacity on the path. Eventually, there are no paths left except those that go through zero-capacity nodes and those zero-capacity nodes can be used to recover the minimal cut.

There are more sophisticated ways of finding a maximum-weight flow, but the complexity of this algorithm is never more than the number of edges in the NFA times the maximum allowable trigram set size. Since we bound both the maximum size of the NFA allowed and the size of the maximum trigram set in the regrams implementation, the complexity never gets out of hand here, and in practice it’s very quick and even out-performs some theoretically faster optimizations like the Edmonds-Karp search order in my tests.

Examples

So what do the results look like? Here are a few examples which you can play with on your own if you have a Go development environment. Just build the regrams commmand line wrapper and follow along:

go get github.com/aaw/regrams

go build -o regrams github.com/aaw/regrams/cmd/regrams

The trigram queries are written with implicit AND

and | for OR, so abc AND (bcd OR bce) comes out looking like abc (bcd|bce):

$ ./regrams 'Hello, world!'

( wo) (, w) (Hel) (ell) (ld!) (llo) (lo,) (o, ) (orl) (rld) (wor)

$ ./regrams 'a(bc)+d'

(abc) (bcb|bcd)

$ ./regrams 'ab(c|d*)ef'

(abc|abd|abe) (bce|bdd|bde|bef)

$ ./regrams '(?i)abc'

(ABC|ABc|AbC|Abc|aBC|aBc|abC|abc)

$ ./regrams 'abc[a-zA-Z]de(f|g)h*i{3}'

(abc) (def|deg) (efh|efi|egh|egi) (fhh|fhi|fii|ghh|ghi|gii) (iii)

$ ./regrams '[0-9]+' # No trigrams match single or double digit strings

Couldn't generate a query

$ ./regrams '[a-z]{3}' # Too many trigrams

Couldn't generate a query

regrams is also available as a Go package, too: just import github.com/aaw/regrams

and then call regrams.MakeQuery on a string to parse a regular expression into a trigram

query. The trigram query returned is a slice-of-slices of strings, which represents a big

AND or ORs: [["abc"], ["bcd", "bce"]] represents abc (bcd|bce).

Optimizations

There’s at least one major optimization that’s possible but isn’t yet implemented in regrams: we could extract node-disjoint paths instead of just node cuts and get more specific queries.

For example, if you ask regrams to generate a query for

(abcde|vwxyz), it’ll generate (abc|vwx) (bcd|wxy) (cde|xyz), which isn’t as specific

as the query (abc bcd cde)|(vwx wxy xyz). (abc|vwx), (bcd|wxy), and (cde|xyz)

represent three distinct cuts in the NFA. If we didn’t stop at node cuts, and instead

augmented the nodes in the cut with disjoint paths, we could avoid this situation

and always return the best trigram query for a regular expression. To do this, we’d

need some algorithmic version of something like Menger’s theorem

that extracts node-disjoint paths from our NFAs that go through only nodes with

non-infinite capacity.

Related Work

codesearch isn’t the only attempt at generating trigram queries from regular expressions. In 2002, Cho and Rajagopalan published “A Fast Regular Expression Indexing Engine”, which describes a search engine called FREE that shares a lot of the ideas found in codesearch, including using an n-gram index to index the underlying documents and generating queries against that index using some rules based on the structure of those regular expressions. The rules are much simpler than those used by codesearch and FREE doesn’t have an actual implementation that I know of.

Postgres also now

supports regular expression search

via an implementation by Alexander Korotkov

in the pg_tgrm module.

Korotkov’s implementation apparently generates a special NFA with trigram transitions after

converting the original regular expression to an NFA, then extracts a query from

that trigram NFA. Korotkov’s implementation seems similar to regrams in that all of

the analysis is done on an NFA, but I don’t understand enough about it to say

anything more. I’d love to read a description of the technique somewhere. It seems

to generate slightly better queries than regrams based on some of the documentation, for

example generating (abe AND bef) OR (cde AND def)) AND efg from (ab|cd)efg, whereas regrams

would generate (abe OR cde) AND (bef OR def) AND efg from the same regular expression.